Pearson, Fisher, Goolsby, and Onken (2005). Using the Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Awards Program Criteria to Determine Business Practices that Differentiate Successful and Unsuccessful Bands. MEIEA Journal Vol 5 No 1, 103-117.

Using the Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Awards Program Criteria to Determine Business Practices that Differentiate Successful and Unsuccessful Bands

Michael M. Pearson, Loyola University New

Orleans

Caroline M. Fisher, University of

Missouri-Rolla

Jerry R. Goolsby, Loyola University New

Orleans

Marina H. Onken, Touro University

International

Characteristics of Good Business Firms – The Malcolm Baldrige Awards

The Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Awards Program was founded in 1975 by the United States Chamber of Commerce and a coalition of business firms. Its purpose was to call attention to the need for building high quality into all aspects of our nation’s businesses. Over the years, firms including General Electric, FedEx, and Rubbermaid have received this award.

The seven judging criteria of the Baldrige Awards are:

- Leadership – What are the distinctive leadership character- istics and traits of this firm?

- Strategic Planning – What is the nature and the extent of planning done by this firm?

- Measurement, Analysis, and Knowledge Management – What information does the firm collect and use in making its decisions?

- Customer and Market Focus – What does the firm do to find, anticipate, and fulfill the needs of its customers?

- Human Resource Focus – What does the firm do to find, anticipate, and fulfill the needs of its employees?

- Process Management – Are processes in place to detect and react to changes in the industry?

- Business Results – Intentions and processes are not enough. In order to be a great firm, you must have results.

The Language of Musicians

The researchers conducted thirty personal interviews with band leaders in order to translate the “business language” of the Malcolm Baldrige judging criteria into the language of performing musicians. The responses from these interviews were entered into a qualitative software package, NUDIST, for analysis.

Based upon the results of the interviews, the authors developed a questionnaire for musicians. It was pre-tested several times with music business classes and working musicians. Table 1 presents all the questions from the questionnaire. Question numbers (the order in which the questions appeared in the questionnaire) are shown in the left-hand column; Baldrige criteria are shown as subheadings (the category numbers refer to the Baldrige criteria presented above). An additional category (Category A) is used for classification questions and questionnaire maintenance items.

Table 1. Questionnaire Items Grouped by Baldrige Category.

Question No. Question Leadership (Category 1) Questions

5 Our musical group has a leader or leaders.

6 Our leader(s) help us perform to our best.

7 Our leader(s) make all decisions for the group.

8 All members of the group participate equally in making decisions.

40 Our group always respects the copyrights of others.

41 Our group always fulfills the terms of its booking contracts. 42 I feel ethically uncomfortable with some business practices of our group. 43 Our group contributes its share of time to charity and community events. 44 Our group never knowingly violates codes or laws in its performances.

Strategic Planning (Category 2) Questions

Our group has a purpose that is agreed to by all members. 10 Our musical group has an artistic vision of what it wants to be. 11 Our group plans as a team. 12 Our group follows its plans. 13 Our group has group goals. 14 Our group sets group goals as a team. 15 We meet regularly to review our goals. 16 We try to get group members’ opinions before making a decision. 17 Everyone in our group knows what each person is supposed to do. 18 Every member of the group works to accomplish our important goals. 19 Everyone in our group contributes equally to running the group. 20 We compare ourselves to other more successful bands to set our goals. 21 Every group member knows our goals.

Customer and Market Focus (Category 4) Questions 30 Our group knows what makes club managers happy with us. 31 Our group tries to please club managers or other venue managers. 32 We contact managers of important clubs or venues regularly. 33 We contact music writers/critics on a regular basis. 34 We regularly contact music stores. 35 We contact radio program directors regularly. 36 Our group receives frequent radio play. 39 Our group asks for feedback from club managers regularly. 50 Our group asks for feedback from its audiences regularly. 51 We talk to members of our audience at our gigs. 52 Our group knows what type of people like our music. 53 Our group tries to please our audiences. 54 We perform certain types of music to please our audience. 55 Our group knows what makes people like our performances.

Measurement, Analysis, and Knowledge Management (Category 3) Questions 22 Our musical group reviews our performances as a group. 23 Our group keeps track of how many people attend our gigs. 24 Our group keeps track of how many CDs and other products we sell. 25 Our group keeps track of its revenues and expenses. 26 Our group knows our local competition. 27 Our group compares its success to other local groups. 28 Our group compares its success to national groups. 29 Group members review the data we track.

Human Resource Focus (Category 5) Questions 56 We all know what is important to each member of our group. 57 Our group accommodates personal priorities of group members. 58 Sometimes we play a gig because one member needs the money. 59 We refer to songs written by one group member as our songs. 60 We thank each other for the work we do. 61 All members believe it is their responsibility to perform well.

Human Resource Focus (Category 5) Questions (continued) 62 We keep track of when each member is available to play. 63 Our group tries to improve the skills of all its members. 64 Generally speaking, everyone in our group works well together. 65 Our group has procedures for selecting new members. 66 Members are encouraged to provide suggestions for improvement. 67 Our group asks members about their satisfaction with the group.

Process Management (Category 6) Questions 1 Our music group performs on a regular basis. 2 We write much of the music we perform. 3 Our group usually performs at one type of gig (like parties). 37 Our group regularly reads music trade publications (e.g., Billboard). 38 We network regularly with more successful bands. 45 We know ahead of time which songs we will practice at rehearsal. 46 We rehearse the songs that we plan to rehearse. 47 We add new songs to our performances on a regular basis. 48 We rotate the songs we play at our performances. 49 We keep our music fresh.

Business Results (Category 7) Questions 4 Our group is successful. 68 Our group has met its objectives as a band. 69 Our group protects its intellectual property (copyrights). 70 Our group has met my individual objectives. 71 We have a growing number of people attending our gigs. 72 We open for more successful bands regularly. 73 Most of our CDs are purchased in the local area. 74 Our group has developed a local reputation. 75 Our group has developed a regional reputation. 76 Our group has developed a national reputation. 77 Our group has developed an international reputation.

Classification (Category A) Questions 78 Our group has gone on a week or longer tour during the past year. 79 Our group has now or has had a record/CD deal with an independent recording

company. 80 Our group has now or has had a record/CD deal with one of the big five

companies (BMG, EMI, Sony, Universal, and Warner). 81 How many members are in your group? 82 How many members have joined your group in the last six months? 83 How many members have left your group in the last six months? 84 How many times has your group performed in the past three months? 85 How many copies of all your combined CDs did your group sell in the past

year? 86 How much money does your group typically earn from a gig? 87 How long has your group performed together? 88 Does someone from outside your group of musicians perform the following

services for your band? Manager 89 Does someone from outside your group of musicians perform the following services for your band? Booking Agent

90 Does someone from outside your group of musicians perform the following services for your band? Lawyer 91 Does someone from outside your group of musicians perform the following services for your band? Accountant/bookkeeper 92 Does someone from outside your group of musicians perform the following services for your band? Publicist 93 Does someone from outside your group of musicians perform the following

services for your band? Publisher 94 Which of the following roles do you play in this music group? Musician 95 Which of the following roles do you play in this music group? Musical leader 96 Which of the following roles do you play in this music group? Manager 97 Which of the following roles do you play in this music group? Songwriter 98 Which of the following roles do you play in this music group? Agent 99 Which of the following roles do you play in this music group? Other 100 What type of music does your group perform?

Research Design of the Study

The researchers identified bands in the state of Louisiana from the mailing list of a regional monthly music industry magazine. 2,845 bands were sent questionnaires. A second mailing was sent after three weeks. 338 usable questionnaires (a twelve percent response rate) was received.

Measuring the Success of a Band

Many different methods can be used to classify a band as successful or unsuccessful. For the purpose of this report only two will be examined.

- Subjective Success – Respondents were asked, “Do you consider your band to be successful?” Some might say they are successful because they make a lot of money. Some might claim success because they are able to play on weekends while working regular jobs during the week. This success rating is a function of the objectives of the band, but it is measured subjectively: the band is meeting its objectives (doing what it wants to do), therefore it is successful.

- Commercial Success – Several measures of commercial success were collected in this research. These measures include touring, securing an independent or national recording deal, CD sales, live performance income, and longevity of the band. Much debate could occur over which of these is the best measure of commercial success.

The authors used cluster analysis to determine statistically the strongest and most distinct success measure for this study. That measure was the number of CDs sold (several of the other measures were strongly correlated and produced fewer statistically significant results.)

Survey Results

Factors Differentiating Subjectively-Measured Successful and Unsuccessful Bands

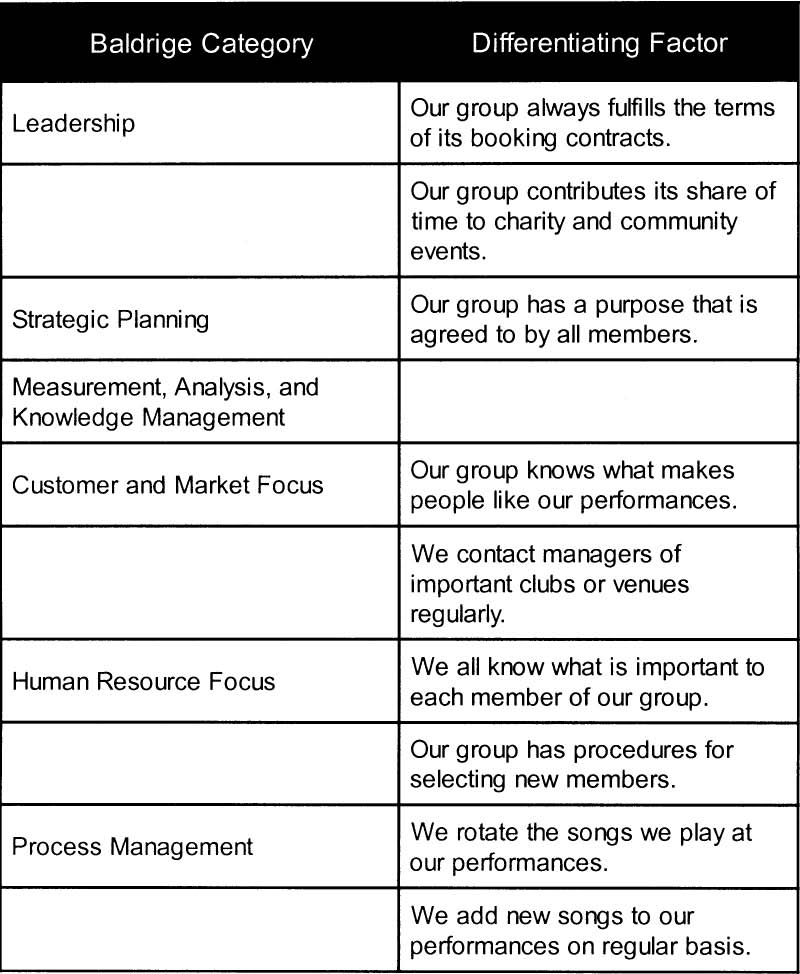

Table 2 presents the factors that significantly differentiated successful and unsuccessful bands using subjective measurement (i.e., based on band objectives). These factors are presented in the categories of the Malcolm Baldrige Award.

The statements that differentiate subjectively-measured successful bands from the unsuccessful bands are few but revealing. The leadership statements that differentiated successful bands were “fulfill booking contracts” and “contributing back to the community.” In the strategic planning category, a significantly higher number of successful bands reported an agreed-upon purpose for the band. Successful bands were differentiated by two statements of customer focus: “know what makes the customer like our performances” and “contact managers of successful clubs and venues regularly.” Among the questions focusing on human resources, successful bands were differentiated by knowing what is important to group members and by having procedures for selecting new members. Within the process management category, successful bands were differentiated by rotating songs and adding new songs. No questions from the measurement, analysis, and knowledge management category differentiated successful and unsuccessful bands.

Overall, successful bands were differentiated by basic and well-bal-anced business practices in all categories except for working with data (measurement, analysis, and knowledge management). This speaks well for the position that successful bands do exhibit at least some of the same management practices as traditional business firms.

Table 2. Differentiating factors between successful and unsuccessful bands (subjectively-measured success).

Factors Differentiating Objectively-Measured Successful and Unsuccessful Bands

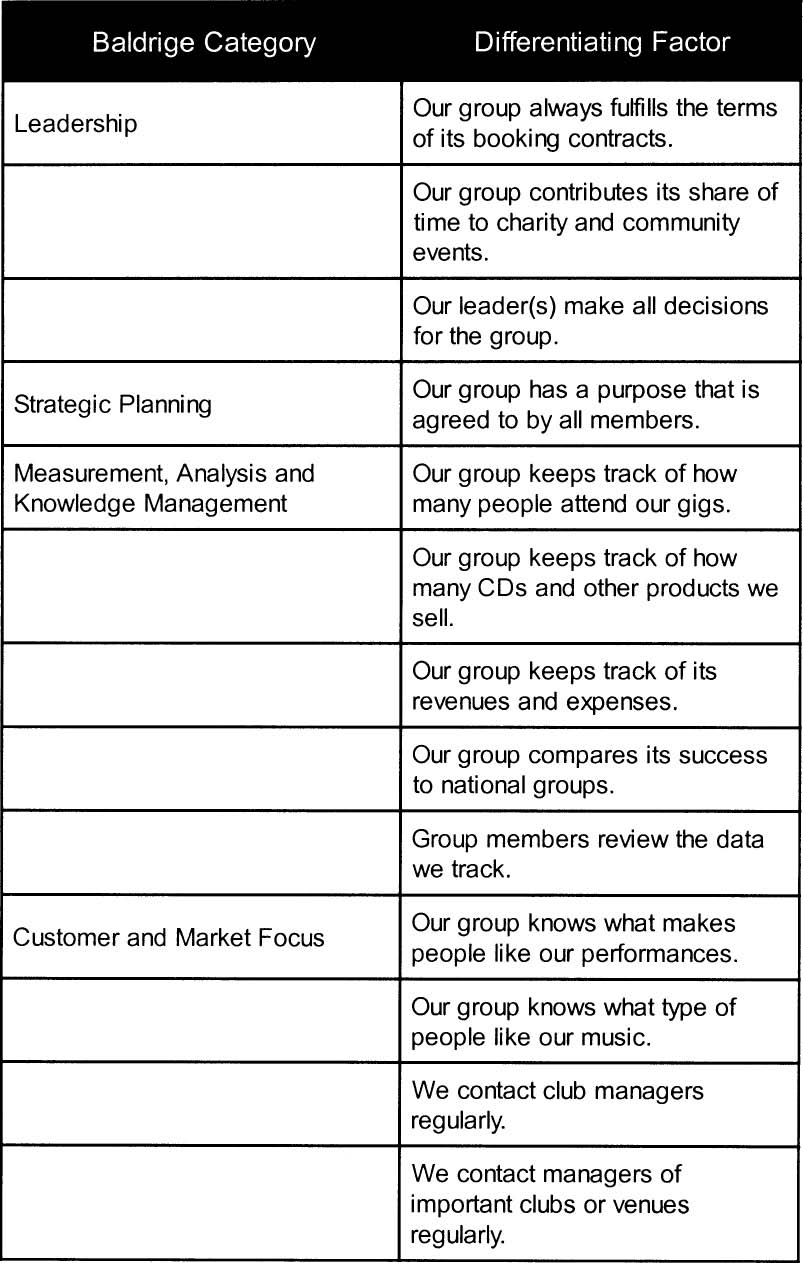

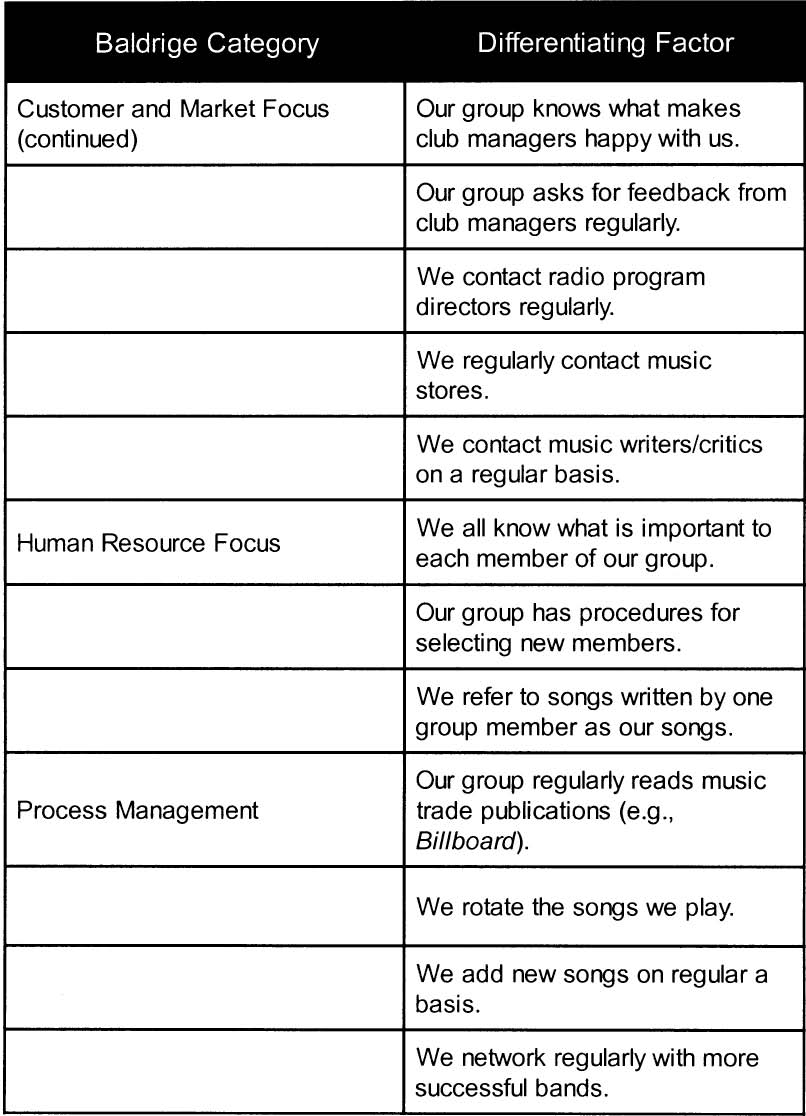

Table 3 shows the items with significant difference in ratings between bands with high CD sales and those with low sales.

Successful bands, as measured objectively by CD sales, operate distinctly differently from less successful bands. Successful musical groups emphasize using information in running the business, focusing on customer groups, and establishing management procedures similar to what is seen in

Table 3. Differentiating factors between successful and unsuccessful bands (objectively-measured success: CD Sales).

Table 3 (continued). Differentiating factors between successful and unsuccessful bands (objectively-measured success: CD Sales).

successful business organizations. They were also differentiated in several other ways. The similarities and differences in management practices between subjectively-measured successful bands and objectively-measured successful bands (as measured by number of CDs sold) are itemized by Baldrige categories below.

Leadership – Successful bands, whether measured by CD sales or a subjective statement, were differentiated by their responses to two statements:

- Our group always fulfills the terms of its booking con- tracts.

- Our group contributes its share of time to charity and community events.

Bands with higher CD sales were also differentiated by their response to the question, “Our leader(s) make all decisions for the group.” This does not indicate that successful bands are autocratically run; the difference actually goes in the opposite direction with successful bands indicating more group decision making.

Strategic Planning – Successful bands, however measured, were differentiated by their response to the question, “Our group has a purpose that is agreed to by all members.” No other differences between successful and unsuccessful bands were found among strategic planning questions.

Measurement, Analysis, and Knowledge Management – There were no statements in this Baldrige category that differentiated successful from unsuccessful bands when a subjective measurement was used. However, a number of differentiating items emerged when an objective measurement (CD sales) was used:

- Our group keeps track of how many people attend our gigs.

- Our group keeps track of how many CDs and other products we sell.

- Our group keeps track of its revenues and expenses.

- Our group compares its success to national groups.

- Group members review the data we track.

Bands that don’t measure and track these items may believe they are successful but they won’t accurately know how they are performing. The lack of differentiation on these items between successful and unsuccessful bands (using the subjective measurement) may be due to the musicians’ lack of accurate knowledge which could result in inaccurate responses.

Customer and Market Focus – Bands with high CD sales showed the same knowledge of what people like about their performances as did the subjectively-measured successful bands. In addition, the following questions differentiated bands with high CD sales from bands that subjectively identified themselves as successful:

- Our group knows what type of people like our music.

- Our group tries to please club managers or other venue managers.

- We contact managers of important clubs or venues regu- larly.

- Our group knows what makes club managers happy with us.

- Our group asks for feedback from club managers regu- larly.

- We contact radio program directors regularly.

- We regularly contact music stores.

- We contact music writers/critics on a regular basis.

This seems to indicate that bands with high CD sales focus more strongly on all customer groups. These bands may take steps that create customer satisfaction and lead to success.

Human Resource Focus – Successful bands, however measured, were differentiated by their responses to two questions:

- We all know what is important to each member of our group.

- Our group has procedures for selecting new members.

Only one additional management practice in this category differentiated objectively-measured successful bands from subjectively-measured successful bands. Bands with high CD sales respond differently to the question about accepting a band member’s individual work as “work of the whole.”

Process Management – Both types of successful bands answered positively to the following questions thus differentiating themselves from the unsuccessful bands:

- We rotate the songs we play.

- We add new songs on a regular basis.

These processes apparently help make a band successful. When success was measured by CD sales, two additional items emerged as differentiating factors:

- Our group regularly reads music trade publications (e.g., Billboard).

- We network regularly with more successful bands.

While these latter two questions didn’t differentiate bands that were rated as successful based on a subjective statement, they may also contribute to the success of a band.

Several Baldrige categories clearly illustrate the differentiating factors in becoming a commercially successful band. Bands considered to be commercially successful monitor a variety of customers, track their results, benchmark against other bands, and update themselves as to what is happening in the music business.

Conclusion

This research, using the Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Awards criteria, shows that many recognized good business practices associated with successful businesses are also associated with successful bands.

What can bands learn from the results of this study? They should work on the basics first. Like the subjectively-measured successful bands, they should:

- have a purpose statement, agreeable to all band members (Strategic Planning);

- fulfill their contracts and take care of their local commu- nity (Leadership);

- know what their audiences like (Customer and Market Focus); and

- take care of the members of their band (Human Resource Focus).

Bands should also work on the areas that differentiated bands with high CD sales by:

- gathering and making use of data (Measurement, Analysis, and Knowledge Management);

- developing and managing processes to find and adapt to change (Process Management); and

- monitoring other customer groups like club managers and radio program directors (Customer and Market Focus).

A clear sense of purpose, understood and shared by all members of the band, is the most important management practice to develop. This is the key ingredient for success with large bands, small bands, large businesses, and small businesses. If this statement of purpose is developed with input from important parties outside the band (family, customers, support personnel, etc.), the chances for business success increase even more.

What can music business educators learn from this study? The Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Award Program was founded to call attention to the need for building quality into all aspects of our nation’s businesses. High quality companies were found to keep their employees longer, receive fewer customer complaints, and have more satisfied and loyal customers. High quality companies also had more sales, larger profits, greater market shares, and higher stock values. Introducing music business students to the philosophy, criteria, and results associated with high quality companies using the Malcolm Baldrige Quality Award Program criteria might be a positive teaching and learning strategy.

Without rational criteria it is difficult to make an objective determination as to whether or not the business practices of a band are of a quality high enough to lead to success. The Malcolm Baldrige Award Program presents us with a set of criteria that has been developed and refined over the years by business leaders.

The authors of this article have carefully followed research procedures to reword the Baldrige criteria into the language of the music industry. Focus groups, personal interviews, multiple pre-tests, and two mailings of the survey were used to refine the language. We have shared the survey questions here so that music business educators will have an established questionnaire to build upon for classes or research. Continual improvement is one of the key themes of the quality movement. We hope that this article will generate this continual improvement.

Future Research

The authors continue to work with data gathered from the survey in an effort to better understand management practices as they relate to music groups. Presently, analysis is being done in the areas of:

- What factors are most important to band members and band leaders in judging the success of a band? (Why do band members consider their band to be successful?)

- Are bands with fewer changes in personnel more success- ful than those with more changes in personnel?

- What leadership style leads to the most successful bands?

- What data are most important to collect and monitor in building a successful band?

- What are the best success measures to use for bands?

MICHAEL M. PEARSON is the Bank One/Thomas C. Doyle Distinguished Professor of Marketing and Area Coordinator of Marketing at Loyola University New Orleans. In addition to his marketing classes, Dr. Pearson teaches music merchandising and music business entrepreneurship classes in the music business program at Loyola. He received his Ph.D. and MBA from the University of Colorado at Boulder, and his B.A. from Gustavus Adolphus College.

CAROLINE M. FISHER, Ph.D. joined the University of Missouri—Rolla as the Chair of Business Administration and the Associate Dean of the School of Management and Information Systems in August, 2005. She came to UMR from Loyola University New Orleans where she taught since 1985 and held the position of Bank One/Francis C. Doyle Distinguished Professor of Marketing in the College of Business. She served as Coordinator of the Marketing Department, directed Loyola’s Six Sigma executive training program, established and ran the Master of Quality Management program from 1993 to 2002, and was the director of the MBA program from 1992 to 1994. Dr. Fisher has taught Customer Focus and Satisfaction, Strategic Quality Management, Statistics, Statistical Process Control, Design of Experiments, Quality Function Deployment, Consumer Analysis and Research, Promotions Management, and E-commerce. She conducts research in the theory of quality management and in customer satisfaction and loyalty. Dr. Fisher’s research has been published in a variety of professional journals. She has co-authored a book on service development and improvement with Quality Press, published in April 2003. She is a Baldrige National Quality Award examiner (1999, 2000, and 2002) and has served as president of the Louisiana Quality Foundation.

JERRY R. GOOLSBY is the Hilton/Baldrige Eminent Scholar in Music Industries Studies at Loyola University New Orleans. In addition to teaching music marketing, music finance, and the senior seminar in the Music Business Program, he also teaches marketing and MBA classes. He received a Ph.D. in Marketing from Texas Tech University.

MARINA H. ONKEN is an Associate Professor at Touro University International, an online university in Cypress, California. She teaches strategic management and international management, both online and in brick-and-mortar classrooms. She received her Ph.D. from the University of Nebraska, an MBA from North Dakota State University, and a B.S. from South Dakota State University.