Journal of the Music & Entertainment Industry Educators Association

Volume 9, Number 1 (2009)

Bruce Ronkin, Editor Northeastern University

Published with Support from

Naxos – A Classic Example of Marketing Principles: A Case Study of the Four P’s of Marketing Techniques as Used by a Classical Music Record Label

Kim L. Wangler

Appalachian State University

Anyone who has shopped for a classical music CD lately has likely noticed the Naxos label with its simple formatted covers and recognizable logo (see Figure 1). What someone might not recognize is the fact that in just over twenty years, Naxos has risen to dominate this small, but potentially profitable niche market. This company identified an opportunity, created a product, priced it right, and now makes and sells more recordings of more repertoire than any other label in this genre—independent or tied to a major record label. The company has also leveraged its licensing rights to create new products that add to the bottom line utilizing material they have previously recorded. Using basic marketing principles, we can gain interesting insights into how an enterprising entrepreneur capitalized on an opportunity and grew a small budget record label into a corporation that has stayed true to its mission to bring classical music to more people, boasts impressive profits, and claims the title of the “world’s leading classical label.”1

History

Klaus Heymann, an international entrepreneur—born in Germany and based in Hong Kong—is the founder and owner (for over twenty years) of Naxos. Heymann began his career as an advertising and promotion manager for Max Braun AG and entered the music industry as a distributor of Bose and Revox equipment in Hong Kong and China. His interest in classical music and background in marketing led him to organize concerts to showcase the equipment he was selling. These concerts were well received. Through them he learned from his audience that many people were interested in buying classical recordings, but they were not available in Hong Kong at that time. Perceiving this need, he began distributing several classical labels of the era.

Due to his interest in classical music and his success presenting concerts in this genre, he was invited to join the board of the Hong Kong Philharmonic. While serving on the board Heymann met his future wife, Takako Nishizaki—a world class violinist. To promote his wife’s career, he stared HK, a record label focusing on Chinese symphonic music, and recorded his wife as a soloist. Based on the success of these recordings, he started Marco Polo, a label dedicated to rare symphonic repertoire of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, which is still in existence today.

When the CD format took hold in the late 1980s, and manufacturing prices dropped, Heymann saw an opportunity to start a budget label whose repertoire would appeal to a broader constituency than the current classical recording market served. He chose the name “Naxos” based on the famous island in Greece and its connotation and association with classical Greek art and culture. Thus, in 1986, with a collection of about sixty CDs recorded by Eastern European orchestras and artists, and a relatively simple mission of, “providing a wide range of good music, well played and recorded and available at a relatively modest outlay,”2 Naxos was born.

Today, still based in Hong Kong, Naxos employs about three hundred individuals worldwide. The company has subsidiaries in the United States, Canada, United Kingdom, Germany, Sweden, Australia, Denmark, and Finland. Products now include over six thousand CDs, many books, DVDs, books on tape (and CD), and various digital offerings. While once scorned by music critics and classical elitists, Naxos has garnered the re-

Figure 1. The Naxos label with its simple formatted covers and recognizable logo.

Figure 2. Klaus Heymann.

spect of many in the industry and proudly touts its numerous awards for recording and performance quality, including several GRAMMY awards.

MARKETING

Marketing is a term that is generally understood by the layperson to be synonymous with advertising. However, anyone who has studied marketing knows that the art and science of marketing is multifaceted. In order to better understand the concepts involved, one should first look at some definitions:

Marketing is the activity, set of institutions, and processes for creating, communicating, delivering, and exchanging offerings that have value for customers, clients, partners, and society at large. (American Marketing Association, http://www.marketingpower.com/AboutAMA/ Pages/DefinitionofMarketing.aspx)

The commercial functions involved in transferring goods from producer to consumer. (Merriam Webster Dictionary, http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary)

Marketing is a social and managerial process by which individuals and groups obtain what they need and want through creating and exchanging products and value with others (Marketing in the Music Industry, Hall and Taylor 2000).

As can be seen by these definitions, marketing is much more involved than just making up a “catchy” television commercial. It involves branding, pricing, distribution, and many other variables related to connecting companies with their consumers. While there are countless ways to approach this complex process, many introductory studies begin with the “4 P’s of Marketing: Product, Price, Place, and Promotion.” By looking at the implications of each of these aspects of creating an exchange opportunity, we can glean a better understanding of what a company is offering and how it is making it attractive to potential customers.

Product

When Naxos was first conceived, the product offering was plain and simple: no frills budget classical CDs. This unique selling proposition of undercutting the average price of other products in the category by over fifty percent was reinforced through an easily recognizable, unpretentious cover design template used for all recordings. When the company first got started, it launched with recordings of familiar pieces that were only differentiated by the low cost. Because of the company’s commitment to focus on repertoire, not on recording the next superstar artist, it has been able to keep prices virtually unchanged for twenty years.

Once the company found its footing, Heymann was able to focus on product differentiation by looking to expand the breadth of repertoire offerings. Now, the company is known as, “…one of the most adventuresome of all independent classical labels.”3 Naxos has gained significant notoriety because of its commitment to twentieth- and twenty-first-century repertoire—a path many labels do not choose to follow. Heymann has fearlessly recorded the likes of Lutoslawski, Penderecki, and Ligeti. He does not claim to make a profit on every new composer recorded, but he does proudly tout his sales in this category, including selling 25,000 copies of a recording of Pierre Boulez sonatas.4

Along with expanding its offerings of new repertoire, Naxos has undertaken projects to record entire cycles of important works including a 75-disc collection of Franz Liszt’s piano music, an Organ “Encyclopedia,” and all of the 500-plus Vivaldi concerti. Naxos has also looked to past recordings by reissuing historic recordings of important performances. However, due to licensing issues explored in the Capital Records, Inc. v. Naxos of America, Inc. (4 N.Y.3d 540, 2nd Cir. 2005) case, many of these recordings are not available in the United States. All these initiatives have allowed the company to now offer over six thousand unique recordings. The company also anticipated the future by recording most of its material over the last ten years in six-channel surround sound, hedging on audio format changes to come.

Today, although many people still equate Naxos with budget CDs, the company—through expansion and strategic partnerships—has extended its product offerings exponentially. Heymann is certainly aware that while the average product life cycle may be ten years from introduction through growth, maturity, and decline, most CDs have a shelf life of twelve to eighteen months with certain classical “evergreens” lasting significantly longer (the Naxos recording of Vivaldi’s Four Seasons being a prime example, having sold over one million copies since its release in 1992). However, because each recording will eventually decline from its peak selling point, he works to increase the profit potential for his recorded music by licensing it for other uses. Naxos has found a lucrative revenue source in licensing deals, such as placement in many high profile movies including American Gangster, Spiderman 3 and Ratatouille as well as in video games and advertising.

Other licensing opportunities have resulted in new products. Naxos now offers a series of books under its brand name that include packages with CDs of Naxos music. Many of these books cater to amateur musicians and aficionados, and others focus on teaching about classical music and musicians. There are also children’s books that introduce this genre of music and the musical instruments to young people. Naxos also has a joint venture with Nicolas Soames to produce audio books. This collection of “books-on-tape” (which, not coincidentally, due to its affiliation with a CD company, was the first to offer audio books on CD5) focuses on literary classics, including unabridged versions of Shakespeare’s plays, a Sherlock Homes series, and Anna Karenina. Not to shun the younger audiences, there are multiple offerings in “Junior Classics” and “Young Adult Classics.” Naxos has also produced a series of DVDs, including a “Travel Series” that highlights the home cities and countries of classical composers such as Mozart (Austria) and Bach (Germany). The DVD series also includes ballets, classical concerts, and documentaries.

Seeing the future moving in new directions, the company’s product mix has expanded to embrace the internet. Naxos is reported to be the first record label to put its entire catalog online–DRM free.6 Classical music consumers have rewarded this initiative with frequent downloading. The company derives a significant percentage of its sales from electronic formats. This has proven important to the company as it has maintained physical product sales, but has shown growth in the digital arena. Naxos has also supplemented its online sales by distributing over 130 other independent classical labels through its ClassicsOnline subsidiary. It also offers a streaming music service at Naxos Web Radio. The site offers over eighty radio channels featuring Naxos recordings ranging from wind band classics to opera, ballet and dance, and a special section on American Jewish music with commentary by Leonard Nimoy.

Also worth mentioning, is the Naxos Music Library service. With 33,000 CDs, and almost 500,000 tracks of music, this service offers a wealth of offerings. This wide range of music includes recordings from the Naxos label as well as BIS, Chandos, CPO, Hänssler, Hungaroton, and Marco Polo. Customers, for a set fee, can access any of this music through a streaming service from any location. This service is also offered to universities across the United States, almost nine hundred of which have taken advantage of this opportunity to provide a source of legal streaming music for their students for study purposes.

There is no question that Heymann is a shrewd businessman. Given the small market for classical music CDs (estimated at three to four percent of CDs sold) it has proven wise for this company to have expanded its product lines, and to have capitalized on the licensing potential for the recorded music that originated with the CDs. Naxos has remained frugal over the years and has adhered to a strict policy of keeping recording costs low and offering upfront payments to artists (with no royalties paid as the product sells). Because of this, and because it has found so many ancillary uses for its products, Naxos, unlike many labels in the classical or pop music industry, have been able to recoup costs within two to three years on ninety percent of its products.7 As for the other ten percent, Heymann states that those projects are undertaken because they are important to the company or to the classical music world, and he is not worried about their profi tability.

Price

Building a company on the premise of undercutting the competi-tion’s prices is risky in any business, but particularly in one that is known for its small market. Heymann readily admits that if the major labels had seen him as a threat early on and had mounted a competing campaign, they could have put him out of business long before the company would have seen any profits. As it was, his label was simply not taken seriously by others in the industry until it had enough of a stronghold and brand loyalty to withstand budget pricing on re-releases by other labels.

One of the marketing principles Klaus Heymann must have understood is price elasticity. This basic economic concept tells us that there is a relationship—albeit different for every product—between price and the quantity that will be sold (see Figure 3). By pricing at the low end of the spectrum, a company is signaling that it is hoping to sell a large number of units, and in fact, will need to in order to make up the profit that could be made by selling at a higher cost. There is no question that Naxos needs to depend on market penetration—gaining a large share of the potential customers—and the development of a larger customer base to turn a profit. This indeed has come to pass with Naxos currently claiming the following market shares (see Figure 4):8

Figure 3. *At the time of the writing of this article, the current market share in the United States was not available from Naxos.

| UK (15%) | Finland (40%) | Sweden (50%) |

| Norway (50%) | Denmark (30%) | Canada (25%) |

| Greece (45%) | South Africa (45%) | Spain (20%) |

| Germany (20%) | United States* |

Figure 4. Naxos market share.

Naxos may also have considered a psychological-based pricing model as opposed to cost-based or even competition-based models in choosing the initial US$6.99 price tag. This price could be perceived as low enough that someone might consider picking up a disk—or maybe even two—as an impulse buy. The fact that all CDs were priced the same also helped make it easy for customers by not forcing them to compare value as they might between various major record label versions of Beethoven’s fifth symphony that might range in price from $8.99 to $17.99. The lack of choices might frustrate classical music elitists, but for the larger population the simplicity has obvious appeal (and in reality, in many cases their ears may not be trained to appreciate the difference between the Bamberg Symphony Orchestra and the New York Philharmonic).

Whether intentional or not, this pricing scheme pushed Naxos to a different target demographic than was typical for classical music at the time. The low price was, and continues to be, attractive to students and to adult amateurs. Fortunately for Naxos, this is a much larger population than the trained professional musician and studied afi cionados. By reaching this broader audience, Naxos has been able to sell the necessary quantity of recordings to remain profitable.

In order to be able to price Naxos CDs where Heymann wanted them, certain deviations from the typical classical music recording contract were, and still are, necessary. The company has come under fire for paying recording artists upfront fees (and small ones, at that) and not offering points on album sales. While some see this as unfair, Naxos continues to have a wealth of artists submitting recording proposals, and, as stated by Angela Myles Beeching, Director of the Career Services Center at New England Conservatory, and noted speaker on the topic of careers for classical musicians, “For many emerging classical artists, Naxos has provided them their first, best, and only real label experience and distribution opportunity.”

Martha Masters, the 2000 winner of the Guitar Foundation of America International Concert Artist Competition, won a recording contract as part of the prize. She felt the “producers were truly amazing and it was a totally first-class operation.” She also says, “I am incredibly grateful to Naxos for everything—it was a wonderful boost to my career”. This is a strong endorsement considering it comes from an artist who received no financial remuneration of any sort. Jeffrey McFadden, a classical guitarist states, “For a very high percentage of artists, the alternative to Naxos would be to self-finance the equipment, studio time, production, and manufacturing costs, and then sell the recording independently.” He goes on to say, “Financing recordings, maintaining a distribution network, advertising, etc, etc. is expensive and time consuming and has to be contracted out by any artist who wants to continue being an artist rather than becoming a small time retailer of a product that, in the classical music world, is aimed at an elusive and tiny market. Naxos is obviously good at this kind of work.”

It is no coincidence that Naxos did not start in this business by recording American orchestras. According to Heymann, it costs about $100,000—even on a strict budget—to record an orchestra in the U.S., and at a profit margin of between 75 cents and one dollar per CD, without help, Naxos would not be able to turn a profit. Fortunately, in recent years, private sponsors have stepped up—donating the necessary funds to get an orchestra a recording that will have worldwide distribution.

Place

Naxos is only able to sell the large quantity of products that it does because of its expansive and well-developed distribution system. According to Randall Foster, Licensing and Business Development Manager for Naxos of America, the fall of Tower Records, a major client of the company, created the impetus for the company to explore new venues for distribution. This led to the company’s music reaching more people than ever. Naxos physical product (mainly CDs, but also DVDs and books) can be found in retail stores across the country ranging in size and scope from mom-and-pop music stores to Best Buy and Barnes & Noble.

It is interesting to note that when Naxos CDs first hit the shelves, many retailers were reluctant to put them in the bins with their high-priced counterparts, reserving a separate section of shelf space for them. The unintended consequence of this product placement was that Naxos, with its distinctive labeling, was set apart and became easy for customers to see and become familiar with, thus helping to build brand recognition for the company. This trend to merchandise these CDs separately has continued and has been a great marketing tool for the company.

Klaus Heymann also furthered the development of the company by correctly predicting the potential of the internet; he was an early adopter of the web as a means to reach his potential customers. Now, under the Naxos umbrella one finds the following web sites:

www.naxos.com – this is a content rich home page for the company. It includes features ranging from educational materials, to new releases, to information on licensing. This is a very complex and deep portal to company information.

www.ClassicsOnline.com – download from nearly 30,000 CDs almost 500,000 tracks from Naxos and the 130 labels it distributes. No physical sales.

www.naxosdirect.com – sells physical product including CDs, audio books, DVDs, and a significant collection of Super Audio CDs (SACD).

www.naxosaudiobooks.com – sells digital downloads of audio books with a link to naxosdirect.com for physical sales.

www.naxosmusiclibrary.com – this gives access to the streaming service of over 500,000 tracks of music on a subscription basis for both individuals and institutions.

www.naxosbooks.com – this site is links to the home site (naxos.com) and provides access to all the books Naxos has published—with links to Amazon.com for purchase.

www.naxosradio.com – for $19.95 per year one can stream over eighty radio stations from this site with genres ranging from American Classics to Cello Chamber Music.

As brick and mortar retail locations continue to reduce shelf space for recordings, these sites have proven to be good business for Naxos. When obscure musical tracks can be kept on the servers for little cost, even very low volume sales (some of Naxos’ tracks sell fewer than ten copies) can translate into a profit—a prime example of Chris Anderson’s long tail theory. And, while some tracks sell only to classical music fanatics, overall revenue from digital downloads has grown to encompass 25% of the com-pany’s revenue.9 If one adds in physical products sold over the internet, Heymann states that these sales provide 75% of total sales revenue.10

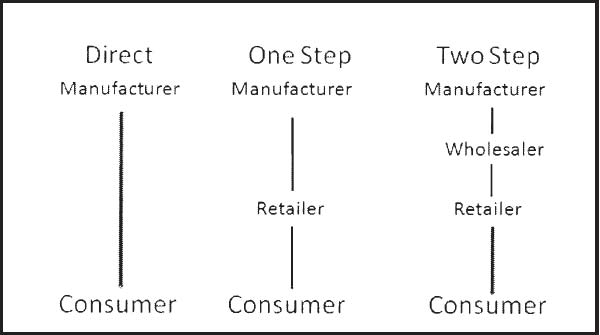

As stated earlier, Naxos’ music can be found in many places. In order to do this, the company employs various distribution models. It sells physical product direct to the consumer through naxosdirect.com and digital offerings at www.classicsonline.com. Beyond the direct distribution model, Naxos employs both one-step and two-step distribution (see Figure 5). Naxos material can be downloaded at iTunes, Sony Connect (before it ceased operations), Napster, Audio Lunchbox, and eMusic as well as other download sites. Physical product can be found online and in stores at well known retailers including Tower Records (online), Amazon.com, Barnes & Noble, Best Buy, and Borders. Heymann states that the next opportunity for the company will be to broaden product placement into lifestyle stores to gain further access to the nontraditional classical music buyer.

Figure 5. Distribution models.

Promotion

Because the profit margins are so thin at Naxos, it depends on volume sales—which makes promotion a very important component of the success of the company. In order to generate demand, Naxos has a well-honed strategy that employs promotion, publicity, and advertising techniques.

Promotion – narrowly defined here as seeking radio airplay, is a mar-keting technique that Naxos depends on. Naxos recordings are put in the hands of all major and many smaller classical radio stations. Through this means, people can actually hear the quality of the music recorded, and are exposed—at least at some of the more adventuresome stations—to music that is not recorded by any other company.

Publicity – Naxos has a myriad of ways to get the word out that do not involve direct payment. According to Sean Hickey, National Sales and Business Development Manager at Naxos of America, Naxos recordings receive nearly fifty reviews a week in print and online publications, with an equal number of commentaries coming from the blogosphere. According to Hickey, these mass media reviews and mentions are very important to the company and are key to driving sales. Naxos artists also create and maintain blogs on Amazon.com to get the word out about their own recordings.

The company has also built strong partnerships with arts organizations that have led to such programs as the Baltimore Symphony’s offer of a free subscription to the Naxos Library when patrons buy season tickets (see Figure 6). This publicity strategy reaches a lot of potential customers and the visibility undoubtedly outweighs the small cost of digital distribution for this promotion. Naxos also has partnerships with other orchestras including the Detroit Symphony, Seattle Symphony, and Early Music America. The company also reaches out to public radio stations by providing CDs for premium gifts during fund-raisers—yet another way to build brand awareness for the company.

Figure 6. Baltimore Symphony Orchestra promotion.

Naxos also expends energy and resources on educational materials. The company is interested in fostering the cause of classical music—and developing a customer base at the same time. It has created publications including, The A to Z of Classical Music and brochures explaining how to enjoy concerts, as well as discs that explore symphonies to further the appreciation and understanding of the art form.

Naxos has also received a great deal of publicity from its commissioning of a series of string quartets by the British composer Peter Maxwell Davies, titled the Naxos Quartets. Although the company has commissioned works in the past, it has never undertaken a project of this nature, and is considered a maverick in the industry for not only recording new repertoire, but actually sponsoring it. The New Zealand Herald touts this as, “…a testament to the faith that Klaus Heymann and his team have put in the health of the contemporary music scene.”11

Advertising – paid advertising is another strategy Naxos uses, although it does not seem to be a primary focus of the company. Library publications are one of the few places where Naxos will pay for advertising in order to reach the institutional library market—a stable and important customer.

Many companies in the market today will use a combination of push (convincing retailers to buy the product and “push” it to the consumer) and pull (building customer demand by reaching out to potential customers who will put pressure on retailers to carry the products they are seeking) marketing strategies. While Naxos does employ select retail programs to entice retailers to carry its product, according to Hickey, “Now more than ever, we focus almost entirely on the demand side of the equation.” Naxos has a well developed digital presence to reach potential customers—a testament to the company’s commitment to be on the cutting edge of technological advances. As part of this e-marketing campaign, Naxos sends out tens of thousands of e-cards every week to potential customers and has an active presence on Facebook, Twitter, and MySpace. The company also has a weekly podcast offered through iTunes and Amazon that boasts a listenership of over 90,000 people per week.

Conclusion

As stated earlier, building any company on the premise of selling based on a low-price strategy is risky—positioning that company in the classical recording market adds to that risk factor and makes the fact that Naxos is recording over $80 million in sales quite remarkable.12 The vision of Klaus Heymann, combined with the exemplary marketing tactics used by the company, has allowed Naxos to produce a breadth of musical offerings unseen at any other label and to earn the reputation of being a, “…pioneering force in a risk-adverse industry.”13

Through the years, Naxos has done a notable job of upgrading the quality of its product—with 75% of its recordings now being done in Western Europe and North America—and significantly expanding product offerings. Even more notable is the fact that by keeping strict controls on artist contracts and recording budgets, Naxos has been able to keep the price of its standard recordings very low—still less than half of the standard major label price in this genre. By having strong offerings in both physical and digital formats, Naxos is able to take advantage of a multifaceted distribution network, garnering a place for its products in a wide array of retail outlets. Finally, Naxos employs a full gamut of promotion tactics that reach customers in a very effective manner. Through the effective use of these four marketing principles, the company has created a viable business model to provide classical music enthusiasts with an unprecedented variety of offerings in the classical genre.

But, this company has no intention of resting on its laurels. There are already plans in the works for developing new audiences and to release material in new formats including preloaded USB devices and fully loaded MP3 players for consumer convenience. And as for new recordings, Heymann plans to continue his quest to record all worthy classical music—and by his estimation, there are about 1.5 million hours of music composed, but there are only about 60,000 CDs of unduplicated repertoire out in the market. That leaves 1.44 million hours of material yet to be recorded, and few who doubt that Klaus Heymann and the Naxos company don’t have the energy, enthusiasm, and expertise to take advantage of this opportunity.

Endnotes

1 Naxos Home Page, http://www.naxos.com 2 Facebook.com, “Naxos,” http:www.facebook.com/pages/Naxos 3 Barrymore Laurence Scherer, “Mr. Heymann’s Opus: The Naxos Cata

log,” The Wall Street Journal, January 15, 2003. 4 Ibid. 5 Klaus Heymann, “Always Innovating, Always Listening to the Market,”

CNN.com, May 19, 2008. 6 Anne Midgette, “A No-Frills Label Sings to the Rafters,” The New York Times, October 7, 2007. 7 Naxos, “About Us: The Philosophy of Naxos,” http://www.naxos.com/ aboutus 8 Naxos, “About Us: Naxos in a Nutshell,” http://www.naxos.com/abou-tus.asp?page=nutshell 9 Alexandra Seno, “Beethoven Goes Digital: Classical Music is Making Money Again,” Newsweek, September 17, 2007. 10 Michael Tumelty, “Leger Lines,” The Herald (Glasgow), October 11, 2008. 11 The New Zealand Herald, “On Track: Contemporary Music Given Fine Treatment,” News, May 23, 2007. 12 Alexandra Seno, “Beethoven Goes Digital: Classical Music is Making Money Again,” Newsweek, September 17, 2007. 13 Elizabeth Blair, “Classical Music: Not Dead Yet,” Morning Edition, December 25, 2006.

References

Adams, George. “An Interview with Klaus Heymann.” Naxos Spoken Word Library, http://www.naxosspokenwordlibrary.com/Subscriber/ AboutUs.asp?active=interview (accessed May, 2009).

Baltimore Symphony Orchestra. “Naxos Online Subscription.” http:// bsomusic.org/main.taf?p=3,23 (accessed May, 2009).

Bazzana, Kevin. “No Need to Lament the Future of Classical Music.” Times Colonist (April, 2009). http://www.ask.com/bar?q=Times+ Colonist&page=1&qsrc=2106&ab=0&u=http%3A%2F%2Fwww. canada.com%2Fvictoriatimescolonist (accessed May, 2009).

CNN.com. “Naxos Facts.” http://edition.cnn.com/2008/BUSI-NESS/03/31/naxos.facts/index.html (accessed May, 2009).

CNN.com/world business. “Klaus Heymann Profi le.” http://edition.cnn. com/2008/BUSINESS/03/31/heymann.profile/index.html

Dart, William. “On Track: Contemporary Music Given Fine Treatment.” The New Zealand Herald, May, 2007. http://www.ask.com/bar?q=T he+New+Zealand+Herald&page=1&qsrc=0&ab=0&u=http%3A%2 F%2Fwww.nzherald.co.nz%2F

Heymann, Klaus. “Always Innovating, Always Listening to the Market.” CNN.com.

Lo, Patrick. “Klaus Heymann Auf Naxos: Cheap Price but Quality Music!—A Case Study of a Successful Western Classical Music Company Founded in Hong Kong.” The International Journal of Arts in Society (2008): 7–37.

Midgette, Anne. “A No-Frills Label Sings to the Rafters.” The New York Times, Arts and Leisure Desk, October, 2007.

Midgette, Anne. “CD Company Slips Quietly Into a World of Creativity.” New York Times, Arts/Culture, November, 2004.

Naxos. http://www.naxos.com (accessed March–May, 2009).

Naxos Books. http://www.naxosbooks.com (accessed March–May, 2009).

Naxos Direct. http://www.naxosdirect.com (accessed March–May, 2009).

Scherer, Barrymore Laurence. “Mr. Heymann’s Opus: The Naxos Catalog.” The Wall Street Journal, January, 2003.

Seno, Alexandra. “Beethoven Goes Digital: Classical Music is Making Money Again, Thanks Largely to Online Downloads.” Newsweek, September, 2007.

Tellig, Sam. “Amazing Stuff: Klaus Heymann of Naxos.” Stereophile http://www.stereophile.com/interviews/254/ (accessed May, 2009).

The Independent. “Klaus Heymann: The Secret of My Success,” January, 2003. http://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/music/fea-tures/klaus-heymann-the-secret-of-my-success-602797.html

Tumelty, Michael. “Leger Lines.” The Herald, October, 2008.

Tumelty, Michael. “Meet Classical Music’s Biggest Record Breaker.” The Herald, May, 2007. http://www.ask.com/bar?q=The+Herald+Gl asgow&page=1&qsrc=0&ab=0&u=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.thehe-rald.co.uk%2F

Tumelty, Michael. “You Read it Here First: Now Naxos is Ready to Take Over the World.” The Herald, December, 2007. http://www.ask. com/bar?q=The+Herald+Glasgow&page=1&qsrc=0&ab=0&u=http %3A%2F%2Fwww.theherald.co.uk%2F

KIM L. WANGLER, MM, MBA, joined the faculty of Appalachian State University in 2005 as Director of the Music Industries Program. Ms. Wangler teaches management, marketing, and music entrepreneurship as well as serving as the faculty consultant for Split Rail Records—the university’s student-run record label. She has served in the industry as President of the board of directors for the Orchestra of Northern New York, House Manager for the Community Performance Series, and as CEO of Bel Canto Reeds—a successful online venture. Ms. Wangler is published through the MEIEA Journal, the NACWPI Journal (National Association of College Wind and Percussion Instructors), Hal Leonard, and Sage Publishing.

KIM L. WANGLER, MM, MBA, joined the faculty of Appalachian State University in 2005 as Director of the Music Industries Program. Ms. Wangler teaches management, marketing, and music entrepreneurship as well as serving as the faculty consultant for Split Rail Records—the university’s student-run record label. She has served in the industry as President of the board of directors for the Orchestra of Northern New York, House Manager for the Community Performance Series, and as CEO of Bel Canto Reeds—a successful online venture. Ms. Wangler is published through the MEIEA Journal, the NACWPI Journal (National Association of College Wind and Percussion Instructors), Hal Leonard, and Sage Publishing.