Journal of the Music & Entertainment Industry Educators Association

Volume 8, Number 1 (2008)

Bruce Ronkin, Editor Northeastern University

Published with Support from

David Blakely: A Life in Music, Politics, Publishing, and Printing

Ava Lawrence

Northeastern University

Very little has been written about David Blakely. Most articles or books that do mention him are really about John Philip Sousa. In those writings Blakely is discussed in the context of his role as Sousa’s manager. This paper focuses more broadly on the important life and career of David Blakely, a leading entrepreneur in the late nineteenth-century American music business. Largely unknown today, David Blakely was one of the most successful artist managers of his time. He represented some of the most popular artists in the world, brought leading European performers to the United States, and even attempted to create an all-female orchestra in a world that wasn’t quite ready for one. In addition to being an important figure in the music industry, he married into a prominent Vermont family, held political offices in Minnesota, and was well known as a newspaper owner, editor, publisher, and journalist in the Midwest.

David Blakely was born in 1834 in East Berkshire, Vermont.1 His family traveled to Syracuse, New York a few years later where Blakely was educated in the public school system. At the age of 13 he began an apprenticeship in the offices of the Syracuse Daily Star. He then moved back to Vermont spending time at the Bradford Academy and the University of Vermont. He left the University of Vermont prior to graduation and moved to Minneapolis to start his own newspaper. In 1875 he was awarded with an honorary A.M. degree from the University.2

In 1858 Blakely married Adeline Prichard Low. Low was part of a prominent family in Bradford, Vermont. Asa Low, Adeline’s father, was instrumental in founding the railroad in that state. The Blakely-Low marriage produced four daughters: Jessie, Pauline (a gifted violinist), Bertha, and Julie. All the daughters shared their father’s passion for music and received instrumental and vocal training in Europe. For five years Blakely would join his family in Europe for the summer.

According to an entry in The Book of Chicagoans: a Biographical Dictionary of Leading Living Men and Women of the City of Chicago, a

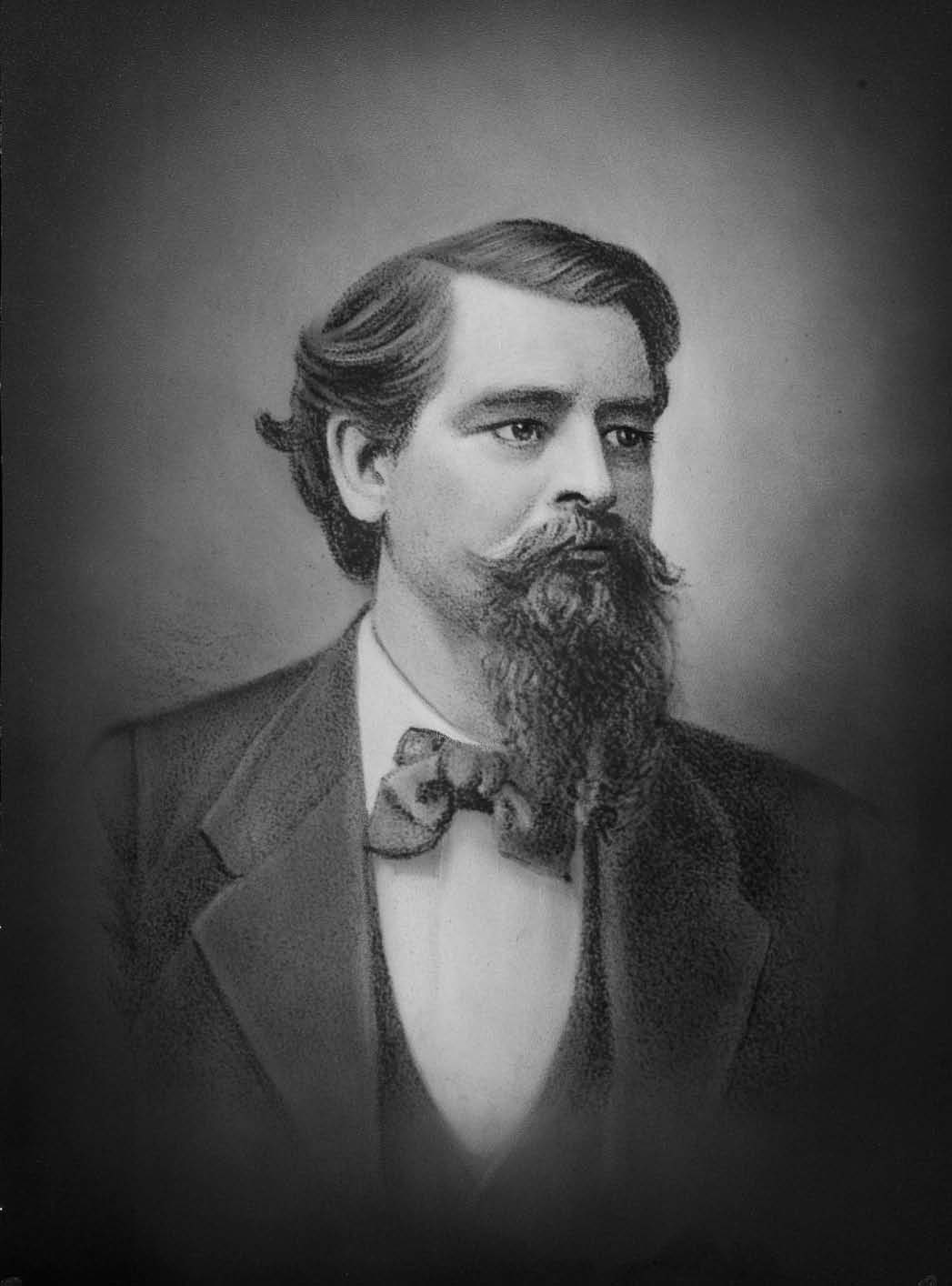

David Blakely (courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society).

Charles Franklin Blakely was born in Danielsville, Connecticut on July 8, 1845 and was adopted by David and Addie Blakely. The entry also states that David Blakely gave him half of the Rochester Post. After the Great Chicago Fire of 1871, Charles founded the House of C. F. Blakely that same year. In 1874 it became known as Blakely & Brown and then later, Blakely, Brown & Marsh. The company finally incorporated under the name Blakely Printing Co. in 1885.3

Many of David Blakely’s summers were spent at the Low family mansion in Bradford. The house had been in the family for generations.

It was usually handed down to the relative who could handle the cost and maintenance of the estate. From the 1880s until 1915 the property was know as the Blakely home. The third floor was converted into a ballroom while the Blakely family lived in the house and was used for parties and concerts. Although it has never been substantiated, it is believed that the Sousa band performed at the house.4 The Blakely home was an important element of the family. Many family members were born in the house and it served as a location for many types of gatherings. It was said to be “a cultural center for the community.”5

Blakely’s professional life was rooted in the newspaper business. He was the founder, editor, or publisher of numerous newspapers, between 1857 and about 1880, such as the Bancroft Pioneer in Mower County, Minnesota, Minnesota Mirror in Austin, Minnesota, Rochester City Post in Rochester, Minnesota, Chicago Evening Post, St. Paul Pioneer (that later merged with the Press to become the St. Paul Pioneer Press), and he helped establish the Minneapolis Morning Tribune. He was also president of the Blakely Printing Company of Chicago—“one of the largest and most prosperous book, newspaper and periodical printing and binding establishments in the country.”6

Blakely enjoyed many great successes in his life but there were a few challenging episodes as well. “When Blakely retired from the editorship of the Minneapolis end of the St. Paul Pioneer Press he confessed to an interviewer that the two-horse act of riding two cities at the same time by one paper is a failure.”7 In the early 1870s he was the Chicago Pension Agent and he owned the Chicago Evening Post. The Great Chicago Fire of 1871 destroyed the Post’s newspaper plant; this is probably what prompted his return to Minnesota upon purchasing the St. Paul Pioneer.

In 1874 Blakely stepped down as the Chicago Pension Agent due to the move. However, he had secured a loan in the amount of $5,000 that he had to repay. He arranged for Miss Ada Sweet, the daughter of the former pension agent, to take over his position. Sweet needed the salary increase that the job would provide in order to take care of her family; her father had died a poor man. Since Sweet spent time working in the pension office with her father, she was familiar with the work. She had been working in the Internal Revenue office when Blakely approached her about the pension agent position. Before turning over the lucrative job to Sweet, Blakely required her to agree to pay off his debt. This took about half of her salary, but even with these payments, Sweet was still making a few hundred dollars more than at her previous job.

Sweet testified before the House Committee on Civil Service Reform in Washington, D.C. about the matter. As a result of the committee’s examination, four resolutions were recommended:

1) That in the opinion of the House, the demanding or accep- tance by any person of money, or any other valuable thing, for himself or another person, as a consideration for real or pretended influence, to be used in procuring appointment to public office, is disgraceful to the individual, prejudicial to the public interest, and leads to inevitable corruption and dishonor.

2) That such misconduct, when found to exist in the case of a public officer, is in the judgment of the House cause for removal.

3) That the Judiciary Committee of this House be directed to report a bill for the definition and punishment of offenses of this nature.

4) That a copy of this report be forwarded to the President of the United States for his information.8

Blakely published an article in his paper the Pioneer-Press denying all allegations.9

Having developed friendships with a number of politicians in the Midwest, Blakely began participating in Minnesota politics while continuing to pursue publishing. From 1861 to 1862 he served as the Chief Clerk of the Minnesota House of Representatives. From 1862 until 1865 he was the Secretary of State of Minnesota. He was also ex-offi cio Superintendent of Public Instruction of Minnesota through the terms of three Republican Minnesota governors: Alexander Ramsey (1860-1863), Henry Swift (1863-1864), and Stephen Miller (1864-1866).

Spending summers in Europe with his family gave Blakely a chance to seek out the very best music the continent had to offer. Having been pleased with its performance, in 1890 he arranged for the Eduard Strauss Orchestra of Vienna to tour America. Eduard Strauss (1835-1916) was the younger brother of Josef and Johann and the son of the elder Johann Strauss. “After the death of his brother, Johann, Eduard was generally recognized as the greatest Kapellmeister of Vienna’s café-houses. It was said that no one else could perform Johann’s waltzes with so much spirit.”10 Blakely’s musical experiences in Europe caused him to wonder why America didn’t have a band equal to, if not greater than, the Garde Rèpublicaine of Paris? This thought led Blakely to discover Sousa.

“Born to sing he has written to live.”11 This is an 1883 quote from gossip columnist Happy John in his “Sunday Budget of Gossip” for the Daily Herald. Although he had a lifelong love of music, he fi rst supported himself as a journalist, editor, and publisher. Blakely had a history of involvement with music. Initially his participation was for pure enjoyment. Like his daughters, he also inherited a passion for music from his father. Blakely taught music during his college vacations from the University of Vermont. While he was living in Minneapolis, he was the Director of the Philharmonic Choral Society and the Mendelssohn Club. Blakely was the music director for the Church of the Redeemer. He was also the man behind very successful concerts and festivals that became prominent around the cities of St. Paul and Minneapolis.

Theodore Thomas (1835-1905), a self-taught violinist from Germany and the first conductor of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, was the director of a very successful festival organized by Blakely. “The receipts during the three days of its continuance, were $27,000, the largest sum ever resulting from a like enterprise, in a city of its size, in the musical history of the world.”12 Christine Nilsson, the Swedish-born operatic soprano and Amalie Materna, Hermann Winkelmann and Emil Scaria, the great Wagner singers, were artists whom Blakely hired for the event. “The chorus, numbering 600, was the joint production of St. Paul and Minneapolis; the Minneapolis contingent, which sung the Wagner choruses from Meistersinger, Lohengrin, etc. being drilled by Mr. Blakely, who had it upon his shoulders also the entire business management of these frequently recurring musical events.”13 “Thomas was the organizer and conductor of the Cincinnati May Music festival in 1873, director of music for the Philadelphia International Centennial Exhibition in 1876, and director of the Cincinnati College of Music from 1878 to 1880. He was the conductor of the New York Philharmonic from 1879 until 1891. He also toured with the American (later National) Opera Company from 1886 to 1887.”14

In 1883 Blakely was noted to be in the Southwest coaching choruses for Theodore Thomas concerts. Along with the Mendelssohn Club, he was also rehearsing male choruses in Des Moines, Iowa and Omaha, Nebraska, all of which participated in Emma Thursby’s concerts on her 1884 tour to favorable reviews. Thursby (1845-1931) was a celebrated American soprano. “Contemporary accounts mention her fl awless coloratura technique, her avoidance of scooping, and the evenness of her instrument throughout its unusually large range.”15

The first Patrick Gilmore tour under the management of Blakely was three years prior to Blakely’s move to his New York offi ce. Gilmore (1829-1892) immigrated to the United States from Ireland in 1849. He was a very important American bandleader who led a number of different bands in the Boston area. Some of his more notable accomplishments include reorganizing the Massachusetts military bands at the request of the governor, supervising the music for the inauguration of Louisiana’s new governor in 1864, touring with his own band, founding a musical instrument company (Gilmore & Wright), and organizing the National Peace Jubilee in 1869. When Gilmore toured, “Blakely always hoped that the local managers would guarantee him a fixed amount, then divide the net after local expenses into approximately 75 percent for the Band and 25 for the local management.”16 It was not until around 1889 that Blakely moved to his office in the Carnegie Building on 57th Street and Seventh Avenue in New York City to further turn his passion for music into a career, arguably, as one of the most successful artist managers in history. Blakely’s employees included Howard Pew, press agent, Frank Christianer, assistant manager, and Jefferson Leerburger, who later became the acting manager of Blakely’s unsuccessful Ladies Symphony Orchestra.

Blakely was serious about creating an all-female symphony orchestra. He scoured the musical world for the best female musicians he could find. He corresponded with Otto Florsheim of The Musical Courier and J.

L. Stager of The Keynote asking if they could recommend female musicians. Blakely eventually placed ads in those trades as well as the publication the World for Female Orchestra Players. He contacted various figures in the music industry for recommendations including Hermann Wolff, the manager of the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra; Herman and Liman, dramatic, variety and musical agents; Henry Wolfsohn, Esq., a prominent agent in New York; and Maud Powell, a noted American violinist who agreed to be his concertmaster. In March of 1891 he corresponded with Fred Bacon, Esq. who was the musical editor for the Boston Herald. In his letters he inquired about musicians from the Eichberg Female Quartette and the Fadette Ladies’ Orchestra. Blakely wrote:

Confidentially, I am organizing a female orchestra, consisting of first class artists, among them being Miss Maud Powell, and other equally fine performers. And I intend to surprise the public one of these days by showing them what the girls can do towards making artistic music in America. I need not tell you that this will be an organization not only fine for women, but fine for men.17

Blakely truly believed that he could assemble a highly talented group of female musicians for his orchestra. Unfortunately this business endeavor was not successful. The primary reason was that many of the women whom Blakely approached were earning more money as music teachers and soloists than they would earn in the orchestra. He simply could not afford the salaries they were requesting.

Even though Blakely’s main client was not a classical musician, his business practices were similar to those of the concert agents in Europe who were representing classical musicians. Current music industry practices are also very similar to both Blakely’s and the European agents of the past.

Blakely used advance-men to check on local advertising, he sold space for advertisements in the concert program book, he routed a tour to maximize its success, he scoured the music world for the very best talent, and he learned what was popular in Europe and applied the formula in America. He even structured a promoter deal much the same way it is done today.

Blakely was working with some of the greatest bands and orchestras of his time: Gilmore, Sousa, Strauss, and others. His formula for managing and promoting musical groups was very successful.

There were also half a dozen others known as “advance men” who would precede the Band on the road by about a week or ten days to check up on the local advertising. These men were temporary employees who were often rehired each season.

Except for minor changes, the printing for all tours was the same. There were lithographs of the Band leader, the Band itself, and the soloists accompanying it. There were posters of three sizes with local time and place information strips to be added. Cuts of the leader and certain soloists were supplied for newspaper articles.18

When Gilmore died, Blakely recognized the opportunity and arranged for Sousa to take his place at the St. Louis Exposition and also for performances at Manhattan Beach. It was a fortuitous career moment that Sousa was ready to step right in and fill the void. There has been much documented on the business relationship between Blakely and Sousa. They entered into a five-year agreement on August 1, 1892 that lasted even after Blakely’s death. Blakely’s estate ended up with half the net profi ts from the final tour during the period of the contract and half of the royalties on all compositions Sousa published before Blakely’s death.19

Blakely died on November 7, 1896. His secretary Julie Allen left the office to run an errand. When she returned to the offi ce Allen found Blakely dead on the floor. About a month before his death he had been involved in a terrible bicycling accident at the house in Vermont. It was unclear if the accident had anything to do with his death. Due to controversy over the cause of Blakely’s death, his body was disinterred in order to perform an autopsy. Doctors representing the Preferred Accident Insurance Company and the Travellers’ Insurance Company were present.20 He was only insured for accidental death, but the cause of his death was noted as apoplexy. It was the family’s contention that the apoplexy was the result of injuries sustained in the bicycling accident.

David Blakely was a man of many talents. He was an accomplished politician, publisher, editor, journalist, music industry manager, and entrepreneur. It is important to learn about Blakely and to recognize his contributions to American music and the American music industry.

Endnotes

1 According to the book Bradford, VT. Burials 1770-1997, written and published by Arthur L. Hyde around 1997, David Blakely’s gravestone lists his birth as December 7, 1834. The book titled Genealogical and Family History of the State of Vermont compiled by the Hon. Hiram Carleton and published by The Lewis Publishing Company in 1903 states that Blakely was born in 1834 in East Berkshire, Franklin County, Vermont. However, the Vermont State Vital Records Office was unable to locate his birth certifi cate. Furthermore, the Minnesota Historical Society records his birth as 1831 in Binghamton, New York. According to the Vital Statistics web page of Binghamton, New York, records were not kept until 1884.

2 Sylvia Bugbee, email message to author, July 19, 2007. 3 John W. Leonard, ed., The Book of Chicagoans: a Biographical Dictionary of Leading Living Men and Women of the City of Chicago

(Chicago: A. N. Marquis & Company, 1905), 65–66.

4 Bradford Historical Society Presents the History of the Low Mansion

(Bradford Historical Society, 1991).

5 Camilla Low, “Camilla Low’s Family Recollections Rich in Lively, Colorful Anecdote: The Low Family An Interpretation By A Great Granddaughter of Asa Low,” The United Opinion (July 22, 1965).

6 “Mr. D. Blakely,” The Musical Courier (February 1893), 20.

7 “David Blakely Retires Minneapolis Paper,” Lake Superior Review and Weekly Tribune, published as The Duluth Daily Tribune 3, no. 105 (September 13, 1883).

8 “Washington. Opening of the Investigation of the Chicago Pension Agency Scandal,” The Inter Ocean 5, no. 39 (May 9, 1876). “Miss Ada Sweet and the Bummer Blakely,” Pomeroy’s Democrat 8, no. 27 (July 1, 1876). “The Chicago Pension Agency Testimony of Ex-Commissioner Baker in Reference to the Case of Miss Sweet,” The New York Times (May 27, 1876).

9 “That ‘Sun Slander’ What Mr. Blakely Has to Say Concerning the Matter,” The Inter Ocean 4, no. 245 (January 5, 1876). 10 David Ewen, “The Vienna Strausses,” The Musical Quarterly 21, no. 4 (1935): 446–474. 11 Happy John, “Happy John. His Sunday Budget of Gossip For the Daily Herald,” Daily Herald (July 20, 1883).

12 “Mr. D. Blakely,” The Musical Courier 26, no. 5 (February 1893). 13 Ibid. 14 Biography of Theodore Thomas, Theodore Thomas Papers, The New-

berry Library, Chicago.

15 John Grazianor, “Thursby, Emma,” Grove Music Online, http://0-www.grovemusic.com.ilsprod.lib.neu.edu:80/shared/views/article. html?section=music.46121. Accessed May 29, 2008.

16 Jon Newsom, Perspectives on John Philip Sousa edited and with an introduction by Jon Newsom, Margaret Brown, “David Blakely, Manager of Sousa’s Band,” (Library of Congress, Music Division, Washington, D.C., 1983).

17 Letter from David Blakely to Fred P. Bacon, Musical Editor, Herald,

New York Public Library, New York, N.Y. 18 Newsom, op. cit. 19 Blakely v. Sousa, (1900). Newsom, op.cit. 20 “Blakely Autopsy Begun,” The New York Times (December 31, 1896).

References

“Autopsy. On the Body of David Blakely, late Manager of Sousa.” Knoxville Journal, December 31, 1896.

Blaisdell, Katharine. “Over the River and Through the Years: Low, Pritchard, and Blakely.” Photocopy of a published article obtained from the Bradford Historical Society, Bradford, Vermont on August 25, 2007. Unable to document the origin of publication or the date of this article, although, it is likely to have been published in the Bradford Journal Opinion.

Blakely, David. Letter to Fred P. Bacon, Musical Editor of the Herald, March 2, 1891. New York Public Library.

Blakely, Mrs. David. Obituary, 1915. Photocopy of a published article obtained from the Bradford Historical Society, Bradford, Vermont on August 25, 2007. Unable to document the origin of publication or the exact date of this article.

“Blakely Autopsy Begun.” New York Times, December 31, 1896. Blakely v. Sousa. No author or publisher indicated, 1900. Bradford Historical Society Presents the History of the Low Mansion.

Vermont: Bradford Historical Society, 1991.

Carletono, Hiram. Genealogical and Family History of the State of Vermont, a Record of the Achievements of Her People in the Making of a Commonwealth and the Founding of a Nation. New York: The Lewis Publishing Company, 1903.

Cipolla, Frank J. “The Business Papers of David Blakely, Manager of the Gilmore and Sousa bands.” Journal of Band Research 13 (1978): 2–7.

Cipolla, Frank J. “Patrick S. Gilmore: The Boston Years.” American Music 6 (1988): 281–292.

Cole, Mrs. W. S. “John Philip Sousa, Great Band Master, Who Died Last Saturday, Once Visitor Here.” The Opinion, March 11, 1932.

“David Blakely.” Union Opinion Special Illustrated Edition, September 1895.

David Blakely Biographical Sketch. New York: David Blakely Papers, 1880-1931. New York Public Library.

“David Blakely Biography.” Minnesota Biographical Project File. Minnesota Historical Society Library.

“David Blakely Dead Has a Fatal Apoplectic Stroke at his New York Of-fice.” Minneapolis Journal, November 9, 1896.

“David Blakely is Dead.” New York Times, November 8, 1896.

“David Blakely’s Death.” Minneapolis Journal, December 29, 1896.

Duluth Daily Tribune. David Blakely; Minneapolis; South; Theodore Thomas, July 25, 1883.

Duluth Daily Tribune. David Blakely; Retired; Minneapolis, September 13, 1883.

Ewen, David. “The Vienna Strausses.” The Musical Quarterly 21 (1935): 466–474.

Happy John. “Happy John. His Sunday Budget of Gossip.” Daily Herald, July 22, 1883.

Haskins, Harold W. A History of Bradford, Vermont: Covering the Period from its Beginning in 1765 to the Middle of 1968. New Hampshire: Courier Printing Co., Inc., 1968. (Written at the request of the Town, as expressed by vote of the annual Town Meeting of March 1, 1966.)

Hinckley, David. “Big Town Songbook Celebrating New York’s Musical Heritage.” New York Daily News, March 28, 2004. http://www.dai-lynews.com/city_life/big_town/v-pfriendly/story/177875p-154744c. html. Accessed May 16, 2005.

Leonard, John W., ed. The Book of Chicagoans: a Biographical Dictionary of Leading Living Men and Women of the City of Chicago. Chicago: A. N. Marquis & Company, 1905.

Low, Camilla. “Camilla Low’s Family Recollections Rich in Lively, Colorful Anecdote.” The United Opinion, July 22, 1965.

“Mr. D. Blakely.” Musical Courier, February 1893.

Newsom, Jon. Perspectives on John Philip Sousa edited and with an introduction by Jon Newsom. Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress, Music Division, 1983.

“Observations.” Minneapolis Journal, April 30, 1896.

Patrick Gilmore Biography. College Park, Maryland: Patrick Gilmore Collection, University of Maryland.

“That ‘Sun Slander’ What Mr. Blakely Has to Say Concerning the Matter.” Inter Ocean, January 5, 1876.

Theodore Thomas Biography. Chicago: Theodore Thomas Papers, New-berry Library.

“Vital Statistics.” City of Binghamton, NewYork. http://www.cityofbing-hamton.com/department.asp?zone=dept-vital-statistics. Accessed May 22, 2008.

Weber, William, ed. The Musician as Entrepreneur, 1700-1914. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2004.

AVA LAWRENCE has worked, specializing in licensing, for a number of entertainment companies in Los Angeles, and New York including Virgin Records, GRP Records, Modern Records, New World Entertainment, and TVT Records/TVT Music, Inc. She is an Assistant Professor of Music Industry at Northeastern University. Professor Lawrence received her

B.S. in Music with a concentration in Music Industry from Northeastern University, and her M.A. in Music Entertainment Professions from New York University. Her main areas of research focus on business trends and significant figures in the music industry. Professor Lawrence is the faculty advisor for the Northeastern University chapter of the Music and Entertainment Industry Students Association.